Table 1 presents an overview of the five CFIR domains and associated sub-domains that were relevant for the implementation of our service quality improvement intervention and it also provides detail on the key challenges identified during implementation. In this section, we provide a summary of the CFIR findings and include participants’ quotes throughout.

1-Innovation characteristics

We described three key points relating to the sub-domains of relative advantage, and design quality and packaging that may weaken successful implementation of our service quality improvement intervention.

Illuminating stakeholders’ perception of the advantages of an intervention and the degree to which it can be adapted and tailored to meet service needs are important factors to address prior to its implementation. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, IAPT services had increased the delivery of psychological interventions by telephone at the time the EQUITy intervention was introduced. The lack of clarity about the potential benefits of its use and its addition to current practices at each service may have weakened professionals’ motivation towards its implementation. Indeed, service leads and practitioners shared these views, as illustrated in the findings below:

“So I think, perhaps, if it wasn’t as established, it would have been really useful to have, you know, a Zoom meeting, initially. What’s it about, what would be useful, what can we get from it”. (Service Lead 4).

“I’d say just discussing telephone working as a whole, because I’d say with the university course, you’re taught to deliver the interventions and taught how to conduct an assessment, you’re not necessarily taught how to develop those telephone skills”. (Practitioner 6).

We found that if a service quality intervention includes multiple components and requires engagement from different stakeholders, providing stakeholders with a clear presentation reflecting the integration of and rationale for the different elements is extremely important in improving the likelihood of implementation success. For instance, the EQUITy intervention involved three elements (i.e., Telephone Recommendations for Services, Skills Telephone Training for Practitioners and Telephone Information Resources for Patients), but service leads and practitioners perceived it as a telephone training intervention instead of a service quality improvement intervention. Findings highlighted there was a lack of awareness from practitioners of two of the three elements of the intervention (i.e., Telephone Recommendations for Services and Telephone Information Resources for Patients) and service leads placed more value and importance on the Telephone Training for Practitioners. Below is a quote from a dialogue with a practitioner and one with a service lead illustrating these findings:

Participant: “I don’t even know where that service recommendations book is, if we’ve had it even.(Practitioner 1)

Interviewer: “Right, so you have no knowledge of that at all?”

Participant: “No, not seen it, I’ve not seen the booklet, so I don’t know. I honestly don’t know if we’ve had them”. (Practitioner 1)

Interviewer: “…what were your initial thoughts about the EQUITy intervention and taking part in the feasibility study when you heard about it?”

Participant: “So, is this just the sort of telephone training?” (Service Lead 3)

Consequently, the implementation of the Telephone Recommendations for Services and Telephone Information Resources for Patients components was compromised, weakening their contribution to the change mechanisms set out in the ToC.

We found that when a service quality intervention targets different key stakeholder groups, the design of materials should be user-friendly but also easily accessible, facilitating communication with members of the team, encouraging participation, ensuring good flow, and allowing editing from different contributors (e.g., service leads, practitioners, and administrative staff). Below is a quote from a service lead illustrating the challenges faced in populating one of the documents provided as part of the intervention:

“[referring to the Telephone Guidelines for Services] I just remember, when I, I took the task on, and I sort of identified the things that we already do, and some that we could perhaps do better, I just remember, when I was trying to use it, to write on it, you know, it was hard to do, and I can’t remember exactly why, now. But it wasn’t an easy document to insert information into”. (Service Lead 4)

2-Outer setting

All mental health services were tasked with increasing remote modalities of working, particularly telephone, during the COVID-19 pandemic. The challenge faced was how to deliver telephone treatments as effectively as those delivered face-to-face. Within the outer setting domain, we found that sub-domains of patient needs and resources and external policy and incentives were the most relevant for our quality service improvement intervention. We outlined two key points that may weaken successful implementation.

We found it was important to explore effective routes to deliver patient information to prevent resources from getting lost among other materials routinely received by patients from mental health services. Since COVID, most services use email to communicate with patients, but most patients taking part in this study could not recall receiving our Telephone Information Resources for Patients. One remembered receiving the EQUITy patient leaflet and said:

“So I remember it [patient leaflet] being quite simple, quite easy to look at and didn’t make it feel like a big deal, which is very nice […] so it can feel very kind of, yeah, overwhelming, whereas something that’s sort of short and simple and not intimidating is really helpful”. (Patient 1)

Patients accessing mental health services appreciated the difficulty of finding the balance between providing a lot of information without this being overwhelming. Some found the information provided by services in general was easy to read and to understand and was sufficient for their needs. Others, however, pointed out that grasping it was much more difficult when feeling unwell and valued information that was presented clearly and simply in a user-friendly manner. This finding became evident from the patients’ data but was also shared by practitioners and service leads. In addition, one service lead highlighted the importance of going through the information with the patient during their first appointment:

“And the importance of, I guess, that the practitioner is introducing it to them, and it’s not just something that’s sent to them which they might just overlook”. (Service Lead 4)

Patients, practitioners, and services leads thought that text-heavy documents could be broken down into sections and the use of colour and diagrams could help make the information less intimidating. A colourful leaflet, such as the one provided as part of the EQUITy intervention, softened the impact of the stark impersonal nature of the NHS appointment letter.

“I just really liked the layout of it, I think the colours are really helpful to break it up. I think even though there is a lot of information on there, I do think it helps splitting them up into different text boxes and the bright colours that you’ve used, I think that does help”. (Practitioner 6)

Findings from service leads and practitioners highlighted that the provision of remote delivery of psychological treatments had increased due to COVID. Prior to COVID, the use of telephone was different across sites, ranging from rarely using telephone to delivering most of the assessments and treatment sessions by this modality at Step 2 care (i.e. guided-self-help) only. Practitioners and service leads anticipated that the vast bulk of work would continue via telephone (and/or video) due to its proven effectiveness:

“There are no noises yet that they’re going back face to face, that if they’re working digitally, we’re going to keep it going that way. So I think there will be more phone and more video”. (Practitioner 5)

“But now it’s 90 per cent telephone and about ten per cent online … But you don’t need all the PWPs being able to see face to face, they should have an allocated, maybe one or two that will pick up those and everyone else carries on, on the phone. So they don’t need to see people, because this has worked well, this works really well”. (Practitioner 1)

“So definitely promoting that, because I think after COVID, the majority will still be telephone work as well, so we’ll have to keep that up and promoting it”. (Service Lead 1A)

Service leads indicated costs will be reduced due to not needing physical space to deliver treatments face-to-face, which is the main driver for more treatments being delivered remotely:

“But I still think that the vast bulk of work will be telephone, and even, sort of, after COVID, you know, we’re looking at giving up clinic rooms because that’s going to be a saving to the service. And really, kind of, reducing that down, so where a PWP in the past might have had two full days in clinic, reducing that down to, sort of, half a day and the rest of that time being done, sort of, over the telephone, via Silver Cloud or

via

video”. (Service Lead 3)

This indicates the relevance of this topic and the importance of ensuring successful implementation of interventions designed to improve the quality of telephone working.

3-Inner setting

The sub-domains of structural characteristics and implementation climate, including tension for change, compatibility, relative priority, and goals and feedback, were the most relevant. In addition, sub-domains related to readiness for implementation such as leadership engagement, resources available and access to knowledge and information were key to understanding organizational commitment to implement a service quality improvement intervention, and its incorporation into routine practice. We described seven aspects that may weaken successful implementation.

Mental health services are stretched and face high staff turnover and if no strategies are in place to engage relevant stakeholders, the incorporation of the intervention into daily practice becomes compromised. For instance, our intervention required practitioners to attend two 3-h online telephone skills training sessions. If attendance is low due to service clinical commitments and/or those attending the training subsequently leave the service, are redeployed or are on sick leave, the implementation of the intervention is at risk of failure:

“I think once we had the training very shortly after that, this [COVID] all started, and I think everybody’s just…because some people have been redeployed, people have been moved left, right and centre, so we’ve not really had much stability”. (Practitioner 1)

“Over the last 12 months when people are getting stressed or they are getting burnt out, that seems to be the sort of, common theme that’s running through”. (Service Lead 3)

To increase the likelihood of success, knowledge gained by practitioners attending the training should be cascaded down to other colleagues and to the service, to ensure sustainability over time.

“If some of the staff are part of that initial training, then that will embed it again. So especially if they’re supervisors, because then they are going, it will percolate down to their supervisees, as well. So, in that way, it’s to keep them advised”. (Service Lead 4)

It is anticipated that the development of strategies to immerse staff not directly engaged with the intervention, i.e. new staff or those unable to attend initially, will be pivotal in ensuring their understanding of the intervention and in identifying their role in its implementation and sustainability in their service.

“But also, we were talking about, when our new staff are coming in – we’ve got 18 PWPs coming in, in March – having a training session for them, solely on telephone work.” (Service Lead 4)

Access to telephone training resources online could prove beneficial to overcome the problem of staff turnover:

“I think, if it was almost like a package that was available to almost have on video, sort of thing, you’ve got that, you know, as staff teams change which they do so frequently, it’s there, it’s readily available, people can access it, people can go on refreshers. I’m thinking, you know, I’ve just had someone come back off six months off on sick leave, and they, sort of, feel that they don’t know anything”. (Service Lead 3)

All services were already using the telephone as a treatment modality when our intervention was introduced, and most services envisage that the increased use of the telephone because of the COVID-19 pandemic will continue. Therefore, improving the quality of telephone treatment for patients, professionals, and services was identified as an area of high priority and interest. Data from professionals highlighted the importance of tailoring service quality improvement interventions for each service, and for its workforce, to guarantee success. For instance, the telephone skills training element of our intervention was reported to be more useful for recently qualified professionals than for those with a few years of experience using the telephone. Nevertheless, the most experienced practitioners highlighted that their confidence in current practice increased, and they had developed new skills and broadened their knowledge. They had also benefitted from reflections and discussions about how to overcome challenging scenarios when using the telephone and it had been a good opportunity to identify “bad habits”:

“I think for me, I’ve been doing it that bloody long now, it’s kind of…it’s not a bad thing to kind of reflect on it and look at bad habits, a lot of it. So although I’m confident in doing phone stuff, because when I did my training, my service literally did all phone, so it’s kind of always been the norm for me. I’m more confident on the phone than I am face to face, weirdly. I just like to be different. So I’ve been doing it that long that learning a bit of theory and stuff is probably a good thing.” (Practitioner 5)

Telephone practices in the services taking part in the EQUITy feasibility study were not perceived as needing a radical change, and in combination with clinical demands and busy workloads, the implementation of the intervention was not identified as a service priority; it is hypothesised this compromised motivation and engagement towards its implementation:

“we’re all just struggling to do our basic job as it is and I think anything extra they just don’t want anything else more than they have to deal with. It’s not been pressed as a priority at the moment I think that might be what it is.” (Practitioner 1)

“I think, real life in some ways took over and they couldn’t make it a priority for them”. (Service Lead 3)

Professionals revealed that implementation goals and strategies to monitor the progress of the implementation of the intervention were not in place; and service leads did not report on providing feedback to their practitioners about it. Clear communication and monitoring processes from service leads and/or team managers relating to the implementation of the different elements of the intervention set from the start may prove fruitful in increasing implementation success.

“I know nobody’s raised it, or had a conversation about it, so it’s just fell by the side”. (Practitioner 1).

“I don’t think we’ve been made aware of anything else with regards to this study at the moment”. (Practitioner 3)

“So just getting those specifics from us of what we’re going to implement first from the recommendations. And maybe could do a follow-up to see if those things have happened.” (Service Lead 1B).

Findings highlighted there was an absence of the use of incentives and rewards to foster implementation. One of the practitioners reported that accrediting the EQUITy training as part of a CPD course could be perceived as a good incentive.

“I suppose the only thing that I can think of really is if it was, for instance…because hopefully, as PWPs moving forward, we will get some accreditation maybe by the BPS. I don’t think we’ll get it via the BABCP, but potentially… I don’t know whether it’s like they will have like a… Not exactly a CPD certificate, but something that would count towards like CPD or something that they can get out of it, if it makes sense. Not exactly like a little reward but some sort of incentive, if that makes sense”. (Practitioner 4)

Leadership engagement with and the accountability taken by leaders and managers for the service quality improvement intervention influenced the success of its implementation. Service leads across sites engaged at different levels with the implementation of each of the three different elements of the intervention. For instance, one lead attended the telephone skills training for practitioners but did not engage with the service booklet. Leads from the other two services did not attend the telephone skills training but one set the training as mandatory for their staff, and both services paid close attention to the Telephone Recommendations for Services and made changes accordingly (details about the implemented changes are reported under the “process” domain). All service leads reported that telephone information resources for patients were delivered by email but the majority of patients could not recall receiving them.

All services reported busy workloads and limited availability of internal resources to receive and implement the intervention, including limited time for staff to attend training sessions due to clinical commitments and subsequent lack of time to discuss implementation and monitor its progress:

“I know that you initially said that we could have it for the whole service, for the whole of the PWPs, but because of obviously targets and contacts and them taking a day out, we weren’t able to give it to all of the PWPs, which is a shame really.” (Service Lead 1A)

“So, you know, from a sort of, capacity point of view we don’t have time to, sort of, send the whole team on this training”. (Service Lead 3)

“You get the contacts taken off, your daily contacts, but your caseload doesn’t change, so you still have to fit those clients in somewhere and it’s where it becomes a bit tricky.” (Practitioner 3)

“For PWPs, usually the reason for doing anything or not doing anything is time, that you just get so caught up in the ever increasing list of treatments that you’re doing and assessments that it does feel like there’s no time for anything else.” (Practitioner 5)

Early discussion and planning around how to incorporate the intervention within existing procedures and available resources could potentially facilitate successful implementation.

A lack of awareness and knowledge about two of the intervention components (i.e. Telephone Recommendations for Services and Telephone Information resources for patients) and how to incorporate each of them into day-to-day work tasks was found in the practitioners’ data:

“I don’t really know. I just thought that we attended the training and then we were having this sort of interview with yourself and that was really all we had to do. I never really picked up on anything else.” (Practitioner 3)

Data have shown there was confusion about who was responsible for distributing the resources to patients, and with respect to when (e.g., before or after the patient assessment appointment) and how (e.g., post or email) they should be distributed. It is hypothesised that greater clarity among team members involved in the intervention around how to implement it in their day-to-day work (i.e. what is needed and from whom) could prove beneficial.

“We have received the leaflets, but we haven’t been told what to do with them”. (Practitioner 1)

4-Characteristics of individuals

The sub-domains of knowledge and beliefs about the intervention provided key information to further understand what requires prioritisation to optimise its implementation. We hypothesised that self-efficacy and individual stage of change sub-domains might not appear to be relevant due to the lack of clarity around how to implement each element of the intervention into daily practice and as a result or regular telephone use during COVID. Below we described two key aspects within this CFIR domain.

Professionals’ beliefs and the value they placed on the intervention are key drivers towards the success of its implementation:

“I think my initial thoughts were actually, this is a really good project to be involved in and something that I personally would love to learn more about. Because I’ve…again I’ve done it for years and years and never felt trained in, sort of, delivering treatment over the phone.” (Service Lead 3).

Individual beliefs about personal capabilities to apply the intervention into routine practice and individuals’ motivation to change their current way of working over the telephone are important in reducing its potential failure. For instance, practitioners who were aware of the patient telephone information leaflet reported this was useful but there were concerns and a reluctance to use it due to fear of overburdening patients. Thus, identifying and challenging these beliefs early on during the implementation phase may remove these barriers to implementation.

The majority of practitioners reported the importance of allocating more time during the telephone training to practise skills and indicated it would be beneficial to incorporate into the training specific psychological interventions such as behavioural activation, or exposure and its associated challenges when using this modality.

Findings from patient interview data provided information about key factors that contribute to a positive telephone treatment experience, including the development of a good therapeutic relationship, receiving personalised care, and feeling listened to by their practitioner.

The skills aiding a good therapeutic relationship reported by the patients were: going at a pace that suited them; guiding things along without pushing; keeping focused; listening and responding; being patient and understanding; being genuinely caring and empathetic; providing reassurance; being informal, warm, and friendly.

Patient interview findings showed practitioners cared about them via listening carefully, using their verbal skills such as by having a soothing voice, remembering and recapping what they had said in previous sessions, checking they were ok, and using appropriate utterances and changing tone of voice. Consequently, this meant that the patient felt comfortable, relaxed, less anxious, more positive, less isolated, and more trusted, facilitating patient openness and engagement in their treatment.

“And she definitely does change her tone of voice, so if I say something that I’m struggling with, you can hear the – I don’t know if it’s sympathy or what, but you can hear that kind of change in her tone of voice that shows that she’s actually properly listened to what I’m saying”. (Patient 1)

Findings highlighted that reviewing progress across the sessions (via the use of outcome measures or assessing/evaluating goals) indicated some improvement and provided a sense of reassurance and/or achievement, which maintained their motivation and engagement.

All except one of the patients indicated that they felt the practitioner personalised the intervention to their individual needs; they reported feeling understood and treated as a person rather than a number/case; they had the feeling that the practitioner ‘was on the journey’ with them.

“Just the remembered, you know, little bits of details, I never had to repeat myself and I never felt like…sometimes you can feel like you know when people have a lot of clients, patients, whatever you want to call them, that they kind of just one rolls onto the next and it gets a bit mixed up, but I never felt like that, I always felt like that he’d obviously read his notes before he spoke to me and refreshed his memory. But it felt like…yeah, I felt like a person, not a number”. (Patient 5)

5-Process

The sub-domains of planning and engagement provided relevant information about increasing the likelihood of implementation success and uptake of our intervention. Below we describe two key aspects.

Data from practitioners and service leads highlighted that no formal planning of tasks related to intervention implementation took place in advance. It is hypothesised that the lack of planning around how to implement and monitor each element of a complex intervention could lead to failure and potentially weaken the mechanism of change. Emphasis on clear planning including a) what, who and how the intervention will be implemented and b) monitoring over time, may increase implementation success.

“So I think the traffic light system is definitely needed to keep it on the agenda. And I think maybe for me, it needs to be like on my agenda with the service manager, when I have my one-to-ones, so she can say, where are you at with that? Are you on amber? When are we going to green? So she can keep it on her radar and it’s brought up at every time or every so often in our supervision session of how well that’s going in regards to implementing those things.” (Service Lead 1A)

There was a shared perception amongst those practitioners interviewed that the lack of engagement of stakeholders such as service leads and team managers in the implementation process had a negative impact. In addition, the lack of clarity about the role of service leads, team managers, practitioners, and other staff from IAPT services (e.g., administrative staff) in the implementation of the intervention and its three different components, appeared to have weakened the contribution to the change mechanisms set out in the ToC. For instance, engagement with the Telephone Recommendations for Services ranged from reading the booklet (no recommendations implemented) to immediately implementing the recommendations identified as most relevant. Examples of implemented recommendations included: addressing safe space and confidentiality within the therapy agreement, allocating time in supervision to reflect on telephone experiences and its challenges, incorporating time into staff induction sessions to discuss uncertainties, and anxieties related to telephone working.

Data suggest that nominating an implementation champion to be responsible for the implementation of the intervention and dedicated to monitoring its progress over time, including identifying and overcoming challenges or resistance from staff, could optimise implementation success.

“I value the telephone work, so it sort of suits me a bit. But having someone to take responsibility for it ensures that things will get done, ensures that, well hopefully, that someone who volunteers for it, you know, is more likely to action it.” (Service Lead 4)

“Maybe just a reminder email or maybe something from whoever organised it, just a little reminder to our managers as something just to remind the staff about that training.” (Practitioner 1)

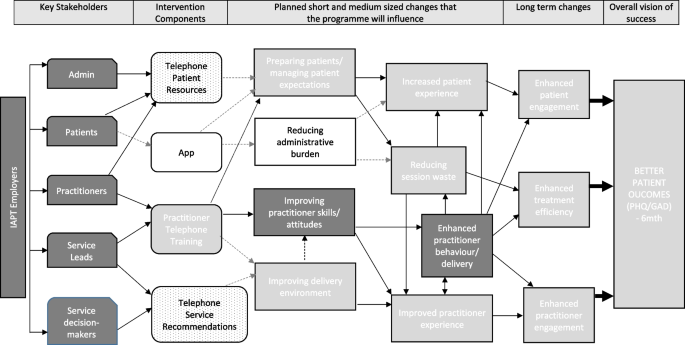

The theory of change for the EQUITy research

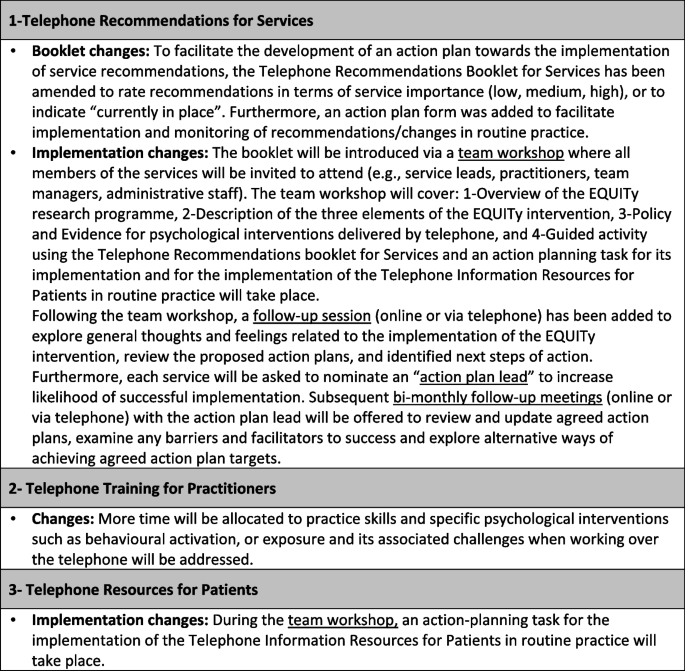

Following findings from this feasibility study, the ToC depicted in Fig. 2 was interrogated, reviewed, and updated by the research team. After agreement with the IRG and the PSC was confirmed, the ToC was amended and pathways to be assessed by qualitative or quantitative methods were represented in Fig. 3. In addition, changes to the content and the implementation of the EQUITy service quality improvement intervention were identified and reported in Fig. 4. Incorporated changes are aimed at improving understanding, guidance, and support to services. Changes are expected to enhance engagement and strengthen the pathways established to promote change and optimise the service quality improvement of, and engagement with, psychological therapies delivered by telephone. The updated version of the intervention and the ToC will be evaluated as part of a randomised controlled trial.

EQUITy Programme: Theory of Change updated following findings from this feasibility study and aimed to be evaluated in a randomised controlled trial

Note: White boxes in grey lines indicate elements removed from the intervention prior to the commencement of the feasibility study. Light grey boxes highlight elements that are potentially diluted/uncertain and indicate additional uncertainty/risk. Grey dash lines indicate diluted pathways/linkages. White boxes with a dotted pattern indicate challenges on the implementation of components weakening anticipated linkages. The dotted line represents an additional linkage. Thick black arrows indicate pathways to be assessed by mainly quantitative methods; the rest of the pathways will be mainly assessed by qualitative methods (via a process evaluation)

Summary of changes to the EQUITy intervention and implementation strategies following findings from this feasibility study and aimed to be implemented and evaluated in a randomised controlled trial

link